|

Short Rounds

Ichabod Crane, U.S.A.

The name Ichabod Crane immediately brings to mind the pompous, superstitious beanpole schoolmaster who is the victim of an elaborate prank in Washington Irving’s tale, “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow.”

Well, there really was an Ichabod Crane, quite unlike Irving’s character, who had a long and honorable career in the United States Army, and is traditionally believed to have “lent” his name to the hapless schoolmaster of Sleepy Hollow.

Ichabod Bennett Crane (1787-1857) was born in New Jersey. He was the son of William Crane, who had risen to major in the Continental Army, serving during the Quebec Campaign of 1775-1776 and with Washington’s army until he lost a leg at Brandywine in 1777; he later rose to general in the New Jersey militia. In January of 1809 Ichabod was commissioned a second lieutenant in the Marine Corps, probably through the influence of his much older brother William, a naval officer. The young lieutenant served aboard the frigate United States, commanded by Stephen Decatur, rising to first lieutenant. In April of 1812, however, Crane resigned from the Marines to accept a commission as a captain in the new 3rd Artillery, commanding Company B (later Battery B, 1st Artillery, and today the 2nd Battalion, 1st Air Defense Artillery).

For much of the War of 1812, Crane served on the northern front. He took part in the operations on the Niagara frontier in mid-1813, including the capture of Fort George and York, in Upper Canada, for which he received a brevet promotion to major dated November 12, 1813. Following the American retreat back into New York, he was stationed at Sackett’s Harbor, on Lake Ontario, where he helped construct Fort Pike.

In 1814, while Crane was serving at Fort Pike, Gov. Daniel D. Tompkins of New York came by on a tour of inspection. Although today largely forgotten, Tompkins was one of the greatest war governors in American history; although a civilian, he had been appointed by the Secretary of War as acting commander of the Northern Department. By chance, one of Tompkins’ aides was Washington Irving, already an established author doing his bit for the war effort as a militia officer.

Following the War of 1812, Crane continued to commanded his company in the Northern Department. In 1820, the company was transferred to Fort Woolcott, a coast defense installation at Newport, Rhode Island, of which Crane assumed command. Promoted to major in the 4th Artillery in late 1825, Crane was transferred to the garrison at Fort Monroe, Virginia. In 1832 Crane was assigned to the command of five companies from Fort Monroe which had temporarily been converted to infantry, and sent to Illinois to serve in the Black Hawk War. That November, he was promoted lieutenant colonel in the 2nd Artillery, and transferred to the army barracks at Buffalo, New York. Early in the Second Seminole War (1835-1842) he commanded elements of the 2nd Artillery in Florida, serving under Col. Zachary Taylor of the 1st Infantry, before returning to Buffalo. Crane performed commendably during the “Patriot War” in 1838 when troubles in Canada threatened to spill over into the United States, managing to control American attempts to smuggle arms to the insurgents without alienating local citizens. In mid-1843 he was promoted to colonel and commander of the 1st Artillery, a largely ceremonial and administrative post. Stationed in Washington, in 1851 Crane was given a secondary assignment as acting governor of the Military Asylum at Washington (later the Soldier’s Home), which he held until November 1853. Crane died in Port Richmond, Staten Island, New York, in October of 1857, still on active duty.

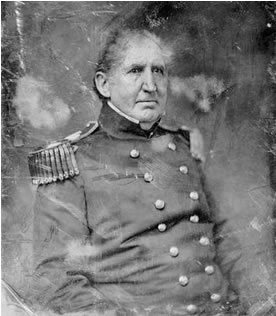

Although their brief encounter at Fort Pike in 1814 was apparently the only time Washington Irving and Ichabod B. Crane ever met, the latter’s name seems to have caught the imagination of the young author. So when, in 1820, Irving came to write “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” it is generally believed that used the name for his the lanky, inept schoolmaster; the real Ichabod Crane was tall and stocky; as can be seen in the attached image, apparently taken during the Mexican War.

Some Crane Kin:

- Son, Charles Henry Crane (1825-1883): After a medical education at Harvard and Yale, he entered the Army as an acting assistant surgeon in 1847. He saw active service in the Mexican War, Third Seminole War, on the frontier, and during the Civil, by the end of which he was Assistant Surgeon General of the United States, becoming Surgeon General in 1882.

- Brother, Joseph H. Crane (1782-1851): An attorney, he settled in Ohio in 1804, and prospered in business and politics, and became a judge. In later life, he was a law partner of Robert C. Schenck, who rose to major general of volunteers during the Civil War. Judge Crane’s, son Joseph G. Crane (1826-1869), served on Schenck’s staff during the war, and rose to major and brevet colonel. While serving as acting Military Governor of Jackson, Mississippi, he was murdered by Col. Edward M. Yerger, a mentally unstable former Confederate officer, in a dispute over a tax assessment; Yerger managed to get off on a legal technicality.

- Brother, William Montgomery Crane (1776-1846), served in the Navy from 1790, seeing action during the Quasi-War with France, on anti-pirate operations in the Caribbean, in the Tripoli War, commanding Nautilus during War of 1812, and the Mediterranean Squadron in 1827, during which time he conducted diplomatic negotiations with the Ottoman Empire, with the honorary title of commodore. He was later a member of the Board of Navy Commissioners and sered as the first Chief of the Bureau of Ordnance and Hydrography, from 1842 until his death by suicide in 1846

- Stephen Crane (1871-1900), the novelist (The Red Badge of Courage), was a distant relative, the men sharing a common ancestor in the eighteenth century.

Tank Casualty Causation in the Korean War

Although the Korean War was essentially an infantryman’s fight, tanks played an important role. The North Korean offensive in June of 1950 that ignited the conflict was spearheaded by numerous Soviet-built T-34/85 tanks, and the U.N. forces quickly committed American Shermans, Pershings, Pattons, and Chafees, as well as some British Centurions.

Although there were no “tank battles” in Korea, on the style of the great mobile clashes in the Western Desert or on the Eastern Front, there were a good many tank-on-tank engagements.

An analysis of 119 combats involving Soviet-built tanks against American-built ones concluded that the latter were about three times more effective in such actions than enemy ones; that is the “kill ratio” of American tanks versus T-34s was about 3:1. In these actions, the American tank fired first about 60 percent of time, and had a 64 percent chance of a first shot kill, whereas even if the Soviet tank fired first, it had only a 38 percent chance of a first shot kill.

But tanks weren’t the major cause of enemy tank losses. Only about a quarter of enemy tanks were killed by American or British tanks, whereas about 75 percent were killed by Allied air power. If for enemy tanks, the greatest danger came from air power, for friendly tanks the greatest danger came not from tanks or air power, but from mines; for every 100 anti-tank mines the North Koreans and Chinese laid, they accounted for one American tank, for a total of about a third of all U.S. tank losses in the war.

|